Mathematical Color Fading

Color and Light

As a kid, I’m sure that we all learned about colors, the color wheel, primary colors and mixing colors, and most of us learned this with paints of some kind. But paint mixing is different than light mixing, in that paint is subtractive, while light is additive. The primary colors in the subtractive color mixing system are red, yellow and blue (known as the RYB set), and the primary colors in an additive color mixing system are red, green and blue (known as the RGB set). This is because those colors are found in the photoreceptors of the human eye.

If you really want to become a super color nerd, you could look into the work of James Clerk Maxwell, or, to dig a little deeper, even the work of Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz.

So what all of that means is that when you paint a surface, for example red, the paint is actually absorbing all of the colors hitting it except for red. The same with blue paint, or yellow or green. Which is why, when you add all of the paint colors together, you get black. Your mixture is absorbing every color.

Conversely, with light, you are hitting a surface with color, so the surface simply reflects that color back. Shine a light with a wavelength of 700nm against a surface, and the surface will reflect that light, and you will see red. Which is why, when you add all of the colors of light together, you get white.

Pigment color wheel on the left; light color wheel on the right.

The concept of color changing

Now that you’ve read up on the Young-Helmholtz trichromatic theory of color vision (and I’m sure you have), you should have a little better understanding of how we can paint with light. It really just comes down to adjusting the percentages of the three colors - red, green, and blue - between 0% and 100%, to achieve the desired color. It would seem to be pretty straightforward stuff, and there are sites that will easily give you both the HEX value (which would look like #FF9999), and the DEC value (expressed as an integer of each color between 0 and 255, like (255, 153, 153)).

Since each of the three colors uses 8 bits, that is how we wind up with 256 possible values for each. While creating any of the 16,777,216 possible colors (256 x 256 x 265, right?) is easy, what happens when we want to smoothly fade from one color to another? There are a couple of ways to do this, so we’re going to look at two options.

Sure it seems simple…

The first method is color fading at its most basic. We take our initial three values - red, green and blue - and adjust the numbers to our second values, so that they start at the same time and finish at the same time. As a simple example, let’s say that your color fade was moving red by +120, green by +15 and blue by -40. Red would start to fade up, then once it got to three, blue would fade down by one; and once red got to eight, green would fade up by one. Back in 2007, Clay Shirky wrote a nice Arduino sketch to do just that. He used percentages of each color, and then converted them to the necessary 0-255 range. And this makes sense; we all get that we can adjust our LED outputs from 0-255.

/*

* Code for cross-fading three LEDs, red, green and blue (RGB)

* To create fades, you need to do two things:

* 1. Describe the colors you want to be displayed

* 2. List the order you want them to fade in

* DESCRIBING A COLOR:

* A color is just an array of three percentages, 0-100,

* controlling the red, green and blue LEDs

*

* Red is the red LED at full, blue and green off

* int red = { 100, 0, 0 }

* Dim white is all three LEDs at 30%

* int dimWhite = {30, 30, 30}

* etc.

*

* Some common colors are provided below, or make your own

*

* LISTING THE ORDER:

* In the main part of the program, you need to list the order

* you want to colors to appear in, e.g.

* crossFade(red);

* crossFade(green);

* crossFade(blue);

*

* Those colors will appear in that order, fading out of

* one color and into the next

*

* In addition, there are 5 optional settings you can adjust:

* 1. The initial color is set to black (so the first color fades in), but

* you can set the initial color to be any other color

* 2. The internal loop runs for 1020 interations; the 'wait' variable

* sets the approximate duration of a single crossfade. In theory,

* a 'wait' of 10 ms should make a crossFade of ~10 seconds. In

* practice, the other functions the code is performing slow this

* down to ~11 seconds on my board. YMMV.

* 3. If 'repeat' is set to 0, the program will loop indefinitely.

* if it is set to a number, it will loop that number of times,

* then stop on the last color in the sequence. (Set 'return' to 1,

* and make the last color black if you want it to fade out at the end.)

* 4. There is an optional 'hold' variable, which pasues the

* program for 'hold' milliseconds when a color is complete,

* but before the next color starts.

* 5. Set the DEBUG flag to 1 if you want debugging output to be

* sent to the serial monitor.

*

* The internals of the program aren't complicated, but they

* are a little fussy -- the inner workings are explained

* below the main loop.

*

* April 2007, Clay Shirky <clay.shirky@nyu.edu>

*/

// Output

int redPin = 8; // Red LED, connected to digital pin 9

int grnPin = 9; // Green LED, connected to digital pin 10

int bluPin = 10; // Blue LED, connected to digital pin 11

// Color arrays

int black[3] = { 0, 0, 0 };

int white[3] = { 100, 100, 100 };

int red[3] = { 100, 0, 0 };

int green[3] = { 0, 100, 0 };

int blue[3] = { 0, 0, 100 };

int yellow[3] = { 40, 95, 0 };

int dimWhite[3] = { 30, 30, 30 };

// etc.

// Set initial color

int redVal = black[0];

int grnVal = black[1];

int bluVal = black[2];

int wait = 10; // 10ms internal crossFade delay; increase for slower fades

int hold = 0; // Optional hold when a color is complete, before the next crossFade

int DEBUG = 1; // DEBUG counter; if set to 1, will write values back via serial

int loopCount = 60; // How often should DEBUG report?

int repeat = 0; // How many times should we loop before stopping? (0 for no stop)

int j = 0; // Loop counter for repeat

// Initialize color variables

int prevR = redVal;

int prevG = grnVal;

int prevB = bluVal;

// Set up the LED outputs

void setup()

{

pinMode(redPin, OUTPUT); // sets the pins as output

pinMode(grnPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(bluPin, OUTPUT);

if (DEBUG) { // If we want to see values for debugging...

Serial.begin(9600); // ...set up the serial ouput

}

}

// Main program: list the order of crossfades

void loop()

{

crossFade(red);

crossFade(green);

crossFade(blue);

crossFade(yellow);

if (repeat) { // Do we loop a finite number of times?

j += 1;

if (j >= repeat) { // Are we there yet?

exit(j); // If so, stop.

}

}

}

/* BELOW THIS LINE IS THE MATH -- YOU SHOULDN'T NEED TO CHANGE THIS FOR THE BASICS

*

* The program works like this:

* Imagine a crossfade that moves the red LED from 0-10,

* the green from 0-5, and the blue from 10 to 7, in

* ten steps.

* We'd want to count the 10 steps and increase or

* decrease color values in evenly stepped increments.

* Imagine a + indicates raising a value by 1, and a -

* equals lowering it. Our 10 step fade would look like:

*

* 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

* R + + + + + + + + + +

* G + + + + +

* B - - -

*

* The red rises from 0 to 10 in ten steps, the green from

* 0-5 in 5 steps, and the blue falls from 10 to 7 in three steps.

*

* In the real program, the color percentages are converted to

* 0-255 values, and there are 1020 steps (255*4).

*

* To figure out how big a step there should be between one up- or

* down-tick of one of the LED values, we call calculateStep(),

* which calculates the absolute gap between the start and end values,

* and then divides that gap by 1020 to determine the size of the step

* between adjustments in the value.

*/

int calculateStep(int prevValue, int endValue) {

int step = endValue - prevValue; // What's the overall gap?

if (step) { // If its non-zero,

step = 1020/step; // divide by 1020

}

return step;

}

/* The next function is calculateVal. When the loop value, i,

* reaches the step size appropriate for one of the

* colors, it increases or decreases the value of that color by 1.

* (R, G, and B are each calculated separately.)

*/

int calculateVal(int step, int val, int i) {

if ((step) && i % step == 0) { // If step is non-zero and its time to change a value,

if (step > 0) { // increment the value if step is positive...

val += 1;

}

else if (step < 0) { // ...or decrement it if step is negative

val -= 1;

}

}

// Defensive driving: make sure val stays in the range 0-255

if (val > 255) {

val = 255;

}

else if (val < 0) {

val = 0;

}

return val;

}

/* crossFade() converts the percentage colors to a

* 0-255 range, then loops 1020 times, checking to see if

* the value needs to be updated each time, then writing

* the color values to the correct pins.

*/

void crossFade(int color[3]) {

// Convert to 0-255

int R = (color[0] * 255) / 100;

int G = (color[1] * 255) / 100;

int B = (color[2] * 255) / 100;

int stepR = calculateStep(prevR, R);

int stepG = calculateStep(prevG, G);

int stepB = calculateStep(prevB, B);

for (int i = 0; i <= 1020; i++) {

redVal = calculateVal(stepR, redVal, i);

grnVal = calculateVal(stepG, grnVal, i);

bluVal = calculateVal(stepB, bluVal, i);

analogWrite(redPin, redVal); // Write current values to LED pins

analogWrite(grnPin, grnVal);

analogWrite(bluPin, bluVal);

delay(wait); // Pause for 'wait' milliseconds before resuming the loop

if (DEBUG) { // If we want serial output, print it at the

if (i == 0 or i % loopCount == 0) { // beginning, and every loopCount times

Serial.print("Loop/RGB: #");

Serial.print(i);

Serial.print(" | ");

Serial.print(redVal);

Serial.print(" / ");

Serial.print(grnVal);

Serial.print(" / ");

Serial.println(bluVal);

}

DEBUG += 1;

}

}

// Update current values for next loop

prevR = redVal;

prevG = grnVal;

prevB = bluVal;

delay(hold); // Pause for optional 'wait' milliseconds before resuming the loop

}

Code by Clay Shirky, 2007

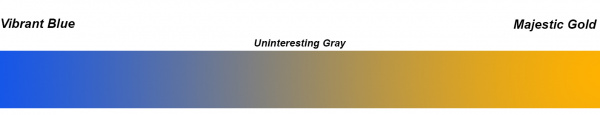

While this method is just fine for many (if not most) applications, it does have its drawbacks. Let’s say your favorite sportsball team wears royal blue and gold as their team colors. It would be cool for your LED wall to fade back and forth between the two colors, right? But what happens to the overall color when it gets about halfway through to fade? Using this mathematical formula, at about halfway through the fade you wind up with your LEDs emitting (138, 132, 116), which is about the least interesting gray color possible. Additionally, it drops the brightness of the LED down to about half.

Mathematically accurate at its center, but a visual snoozer to be sure

Solving the issue with math!

Suppose that for your killer NYE party, which is always the most technologically advanced of any NYE party in your area, you want to fade your room lighting from Pantone’s 2018 color of the year, Ultra Violet, to their 2019 color of the year, Living Coral (and I mean, come on, why wouldn’t you want to do that?). Now you need to create a smooth fade from (95, 75, 129) to (250, 114, 104). We’ve learned that simply fading each of our three colors directly and simply can return some less than exciting moments through the middle of the fade, so how can we avoid this? By throwing a little trigonometry at it!

Pantone’s 2018 and 2019 colors of the year. I think here at SparkFun we’re just going to stick with red.

Now I know that even seeing the word “trigonometry” tends to elicit a fight-or-flight response from most people, but stay with me, this won’t be that terrible. We’re going to be using the sine function, but thanks to sin() within the Arduino IDE, we don’t have to do much math at all!

Okay, we’ll still need to do SOME math. Instead of using integers, we’re going to use floating-point values. In Arduino terms then, instead of using int, we’ll be using float, giving us the ability to use decimal points. This is important here, because A) we will be using things like Pi and radians, and will need numbers like 6.283, and B) sine uses a range of -1 to 1.

A quick sine primer

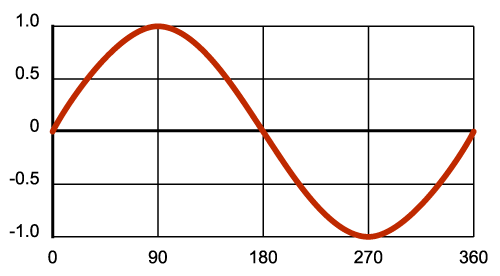

When you input a number into a sine function, you’re actually entering an angle. By running the angle from 0 to 359 (remember, in a circle, 0° and 360° are the same, so if we start at 0, we have to end at 359), we complete one full circle, and our sine wave completes one full circuit.

Degrees of a circle, and their corresponding sine wave

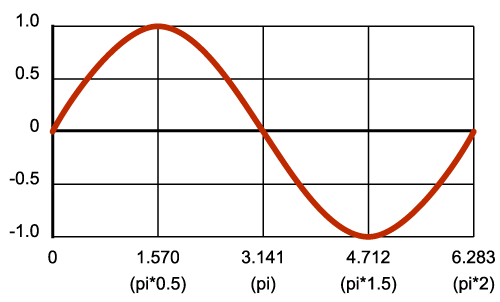

I mentioned that we were going to be using radians, and here’s why. Sin() doesn’t care about us and our degrees of a circle, sin() wants the information in radians. Since we know that a radian is a length on the arc of a circle equal to its radius, and that on any circle that equals about 57.2958°, and that it takes about 3.14159 radians to get halfway around the circumference of a circle, we can redraw our graph depicting radians just as our Arduino wants it.

This is what a sine wave looks like in its natural habitat.

And finally, we know that our illumination range is from 0 to 255. We just need to map our output to meet this range. You may be familiar with the map() function in Arduino, but there’s a simpler way to do this in our case. The most basic equation for sin() is:

out = sin(in)

We can take our sine range of -1 to 1, and adjust it to anything we want, with this line:

out = sin(in) * range + offset

So if we want want the output of our LED to be 0 (off), we would need an input of 4.712. Or, if we wanted our led at 255 (full power), we would need an input of 1.570. But what if we wanted to go from 0 to 255? Do we need to go backward? Not at all. Since our sine wave is continuous (or cyclical), we can continue counting forward and just add Pi to our starting number. Try running this code:

void setup(){

Serial.begin(9600); //Setting up our Serial conection

}

void loop()

{

// do input, etc. here - as long as you don't pause, the LED will keep pulsing

float out;

static float in = 4.712;

if (in < 7.853){ // the sum of 4.712 + 3.141

in = in + 0.01; // not the most efficient, just keeping it clear for demo purposes

}

out = sin(in) * 127.5 + 127.5; // this maps our sine wave, from -1 to 1, to out LED output, 0 - 250

Serial.println(out); // prints the output

delay(100); // just to give us a little breathing room

}

By watching the output to our serial monitor, we will see the numbers go from 0, when the input is 4.712, up to 255, when out input gets to 7.853. This gives us a little insight into how, when used for each of the three colors, this can give us a very nice, non-linear fade.

One thing to notice is the “static” modifier in the above declaration of “in.” If we didn’t use this, “in” would be initialized to 4.712 each time loop() loops, which would keep the LED output permanently at 0. By adding this modifier, you’re telling the compiler to not keep initializing that variable every time we go through the loop.

This is just a small peek into color changing by doing more than just moving linearly from one output number to another. If we are really to examine color and how it is perceived by the human eye, we have a lot more digging to do on the subject. Next time, we’ll not only play a little more with color changing with sine waves, but we’ll also examine playing with HSV - that’s hue, saturation, and value - to move through colors. Additionally, we’re also going to look into CIELAB color space. Because as our parents learned watching Schoolhouse Rock, knowledge is power!

Via Westline T2B http://www.rssmix.com/

Comments

Post a Comment